Nuclear attack is a reality not only in Hawaii, what to do if it happens ?

Hawaii was under a real attack this morning. This was real even if the physical attack emergency alert was canceled and no bomb hit the Aloha State. It was a real wake up calls for visitors and residents alike. The fact people had to think for almost an hour about their upcoming end was a torture experience many visitors will remember when booking their next Hawaii trip for a long time to come. It was not a drill.

The false emergency message instructed every person in Hawaii to look for shelter.

There was nothing explained where and what or how?

It caused panic among visitors and locals alike not knowing what to do, many calling their wifes, husband, parents, sisters, son, and daughters to tell them they love them.

This Saturday morning was a nightmare for everyone in Hawaii and it was unnecessary. There is no excuse for someone to be able to press a wrong button. The governor’s apology was laughable if it wasn’t that serious of a situation.

There is no excuse that it was impossible in Hawaii to call 911 for more than 40 minutes from mobile phones and most home or office phone.

There should have been a plan two to make sure emergency calls are responded to. A simple recording saying there was no threat and to stay on the line for any other emergency would have done it.

[embedded content]

Washington DC, the national capital region has a plan in place in case of a nuclear attack on the United States. Click here to read the details (PDF)

Read the instruction in place by the Federal Government

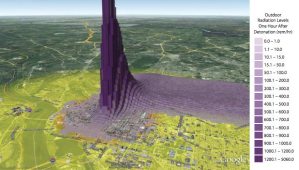

The following is based on recent analysis and recent US Federal Guidance and applies to an IND detonation in any location. Subsequent sections describe specific regional response actions to support the implementation of the guidance based on analysis of the hypothetical 10-kT IND detonation in the NCR. Considerable guidance and information on response to an IND have been recently published by the Federal government, national scientific councils, and other organizations as detailed in the following paragraphs. Recent research over the last few years has helped to greatly improve our understanding of appropriate actions for the public and responder community to take after a nuclear detonation. Much of this research was recently highlighted in a National Academies Bridge Journal on Nuclear Dangers, the content of which is used extensively in the present document. The Federal Planning Guidance for Response to a Nuclear Detonation was developed by an interagency Federal committee led by the Office of Science and Technology Policy, 2nd Ed, June 2010 (EOP, 2010).

This interagency consensus document provides excellent background information on the effects of a nuclear detonation and key response recommendations. Its definition of zones (damage and fallout) is the standard for response planning and should be integrated into any planning process. The National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurement (NCRP) Report No. 165, Responding to a Radiological or Nuclear Terrorism Incident: A Guide for Decision Makers, was released in February 2011 and is a national standard that supplies the science and builds on many of the concepts of the Planning Guidance. For public health information, an entire edition of the journal for Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness was dedicated to public health issues associated with the aftermath of nuclear terrorism. All articles are available for free download. Key Response Planning Factors for the Aftermath of Nuclear Terrorism developed by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in support of the DHS preparedness activity was released in 2009.

DHS Strategy for Improving the National Response and Recovery from an IND Attack, April 2010, breaks the initially overwhelming IND response planning activity down into 7 capability categories with supporting objectives. This can be a valuable document to guide a state and regional planning process as a lot of work has already gone into time phased capability requirements for Doctrine/Plans, Organization, Training, Materiel, Leadership, Personnel, Facilities, and Regulations/Authorities/Grants/Standards.

“This document is for official use only and can be found on the Improvised Nuclear Devices Channel of the Lessons Learned Information System (www.LLIS.dhs.gov). Public Response Priorities The brilliant flash that can be seen for hundreds of miles can temporarily blind many of those who are outdoors even miles from a nuclear explosion. The explosion can turn several city blocks into rubble and may break glass over 10 miles away. Dust and debris may cloud the air for miles, and fallout that produces potentially lethal levels of radiation to those outdoors falls in the immediate area and up to 20 miles downwind. It will be initially difficult for those directly affected to assess the scale of devastation. On a clear day, a mushroom cloud might be visible from a distance, but the cloud is unlikely to keep a characteristic shape more than a few minutes and will be blown out of the area in one or more directions in the first few hours

. The most critical life-saving action for the public and responders is to seek adequate shelter for at least the first hour. The scenario discussed in this document is just one of a broad range of possible fallout patterns, yields, and detonation locations. It is important not to plan to a particular scenario, but rather to plan to accomplish key objectives regardless of specifics.

Unfortunately, our instincts can be our own worst enemy. The bright flash of detonation would be seen instantaneously throughout the region and may cause people to approach windows to see what is happening just as a blast wave breaks the window.

For a 10-kT detonation, glass can be broken with enough force to cause injury out to 3 miles and can take more than 10 seconds to reach this range. Another urge to overcome is the desire to flee the area (or worse, run into fallout areas to reunite with family members), which can place people outdoors in the first few minutes and hours when fallout exposures are the greatest.

Those outside or in vehicles will have little protection from the penetrating radiation coming off fallout particles as they accumulate on roofs and the ground. Sheltering is an early imperative for the public within the broken glass and blast damage area, which could extend for several miles in all directions from a blast. There is a chance that many parts of the area may not be affected by fallout; however, it will be virtually impossible to distinguish between radioactive and nonradioactive smoke, dust, and debris that will be generated by the event (see Figure 5). Potentially dangerous levels of fallout could begin falling within a few minutes.

Those outdoors should seek shelter in the nearest solid structure. Provided the structure is not in danger of collapse or fire, those indoors should stay inside and move either below ground (e.g., into a basement or subterranean parking garage) or to the middle floors of a multi story concrete or brick building.

Those individuals in structures threatened by collapse or fire, or those in light structures (e.g., single story buildings without basements) should consider moving to an adjacent solid structure or subway. Glass, displaced objects, and rubble in walkways and streets will make movement difficult. Leaving the area should only be considered if the area becomes unsafe because of fire or other hazards, or if local officials state that it is safe to move Efforts should be made to stabilize the injured through first aid and comfort while sheltered. Even waiting a few hours before seeking treatment can significantly reduce potential exposures.

Fallout is driven by upper-atmospheric winds that can travel much faster than surface winds, often at more than 100 miles per hour. Outside the area of broken windows, people should have at least 10 minutes before fallout arrives for the larger multikiloton yields. If the detonation were to happen during daylight hours on a day without cloud cover, the fallout cloud might be visible at this distance, although accurately gauging direction could be difficult as the expanding cloud continues to climb and possibly move in more than one direction. Provided atmospheric conditions do not obscure visibility, dangerous levels of fallout would be easily visible as particles fall. People should proceed indoors immediately if sand, ash, or colored rain begins to fall in their area.

At 20 miles away, the observed delay between the flash of an explosion and “sonic boom” of the air blast would be more than 1.5 minutes. At this range, it is unlikely that fallout could cause radiation sickness, although outdoor exposure should still be avoided to reduce potential long-term cancer risk. The public at this distance should have some time, perhaps 20 minutes or more, to prepare. The first priority should be to find adequate shelter. Individuals should identify the best shelter location in their present building, or if the building offers inadequate shelter, consider moving to better shelter if there is a large, solid multistory building nearby.

After the shelter itself is secured, attention can be given to acquiring shelter supplies such as batteries, radio, food, water, medicine, bedding, and toiletries. Although roads could be initially unobstructed at this range (~20 miles), the possibility of moving the numerous people at risk before fallout arrives is highly unlikely, and those in traffic jams on the road would receive little protection from fallout.

Click here to read the more details. (PDF)