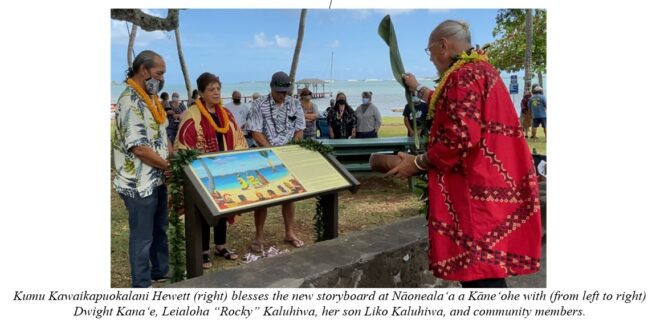

New Historical Storyboard of Native Hawaiian History at Nāoneala‘a a Kāne‘ohe Park

Pictured: Kumu Kawaikapuokalani Hewett (right) blesses the new storyboard at Naoneala’a a Kane’ohe with (from left to right) Dwight Kana’e, Leialoha “Rocky” Kaluhiwa, her son Liko Kaluhiwa, and community members.

Singing over the gusty tradewinds on a Windward O‘ahu Aloha Friday, longtime Kāne‘ohe resident Dwight Kana‘e strummed his ukulele and serenaded the community with an original tribute to a small but significant windward park, Nāoneala‘a a Kāne‘ohe.

The performance was part of a blessing ceremony last week marking the renaming of the City park, formerly known as Kāne‘ohe Beach Park, and the unveiling of a donated storyboard describing the historical significance of the 1.05-acre park. Here is a brief summary of that history, with the entire storyboard narrative provided at the bottom of this announcement:

In 1867, noted Hawaiian historian Samuel Kamakau tells the story of how this area came to be known as Nāoneala‘a, meaning “the Sands of La‘amaikahiki”, after the famous chief La‘a inherited O‘ahu following the death of ‘Olopana. In 1737, a peace accord was struck at this location by the chiefs of O‘ahu and Kaua‘i, all adorned in awe-inspiring attire and accompanied by wa‘a lining the ocean from Mōkapu to Nāoneala‘a.

The renaming of the park, storyboard research, content, and placard were spearheaded and gifted by the Ko`olaupoko Hawaiian Civic Club, via City Council Resolution 19-235, as part of their cultural awareness program. Additional funding for this effort was contributed by the National Geographic Society, the Awesome Foundation, and the Ko‘olau Foundation. The City extends a fond mahalo to these organizations and to the community surrounding this park for their kākou care of this public facility.

“It’s a blessing to be part of this because it’s an awesome example of reclaiming ‘āina and giving this place back its dignity and history by sharing the story of Nāoneala‘a, and by creating a storyboard,” said Honolulu Department of Parks and Recreation’s Deputy Director Kēhaulani Pu‘u at the ceremony. “It’s an example of the values we want to instill in our communities so they can come to love and respect (mālama) these places — our parks.”

Full Storyboard Narrative:

In ancient times, this area was named Nāoneala‘a, for the famous chief who once lived here a long time ago. In 1867, noted Hawaiian historian Samuel Kamakau tells the story

“There was a man at Hanauma named Ha‘ikamalama. When he heard sounds from the sea, he wondered what it was. It was the sound of the big and little drum, therefore he thumped the rhythm on his chest with the tips of his fingers. The sound seemed to come from the sea on the Ko‘olau side, so he sailed to Makapu‘u. He saw them going by on the ocean, so he went by land until he saw the canoe heading toward Kawahaokamanō. He guessed that they were going to Kāne‘ohe in Ko‘olaupoko. When the canoe reached Wai hau palua (Waikalua), he ran to the shore, with his fingers beating the rhythm and he chanting the chant to Kupa…When La‘a and the men on the canoe noticed this, they were astonished. He knew their names through their playing of the kā‘eke. La‘a threw out some sand as a resting place for the canoes. This place is now called Nā-one-a-La‘a (La‘a’s sands). It is in Kāne‘ohe.”

“La‘a, that is, La‘a-mai-Kahiki, was so named for his coming from Kahiki. After the death of ‘Olopana, the kingdom was inherited by La‘a, and he heard from Kila and others that Hawaii was a fertile land, and that the people were great farmers and keepers of fish in fish ponds. O‘ahu was the richest of all, so La‘a became determined to come here to Hawai‘i…

At Nāoneala‘a, the chief built three heiau, one of which was named Kalaoa. Perhaps the area is best known, however, as the site where the chiefs of all the islands gathered to make peace. Kamakau describes this important place in the history of the Hawaiian people: “It was in January, 1737, that the two hosts (Alapai and Peleioholani) met, splendidly dressed in cloaks of bird feathers and in helmet-shaped head coverings beautifully decorated with feathers of birds. Red feather cloaks were to be seen on all sides, both chiefs were attired in a way to inspire admiration and awe, and the day was one of rejoicing as that of the ending of a dreadful conflict. So it was that Peleioholani and Alapai met at Nāoneala‘a in Kāne‘ohe. The canoes were lined up from Ki‘i at Mōkapu to Nāoneala‘a, and there on the shore line they remained, Alapai alone going on shore. The chiefs of O‘ahu and Kaua‘i and the fighting men and the country people remained inland, the chief Peleioholani alone advancing. Between the two chiefs stood the counselor. Naili first addressed Peleioholani and said, ‘When you and Alapai meet, if he embraces and kisses you, let Alapai put his arms below yours, lest he gain the victory over you.’ This is therefore to this day the practice of the bone-breaking wrestlers at Kapua and at Nāoneala‘a. Alapai declared an end of war with all things as they were before, the chiefs of Maui and Moloka‘i to be at peace with those of O‘ahu and Kaua‘i; so also those of Hawai‘i. Thus ended the meeting of Peleioholani with Alapai.”

The area eventually fell under the jurisdiction of the City & County of Honolulu and a maintenance yard and later park was developed and named “Kāne‘ohe Beach Park”. In 2019, it was renamed “Nāoneala‘a a Kāne‘ohe”.